Your Roadmap to Active Retirement: Understanding and Managing Arthritis

Last Updated on December 8, 2025 by David

Arthritis is one of the most widespread chronic health conditions globally, and managing it successfully is key to ensuring an enjoyable, active retirement. If you are approaching or are already enjoying your retirement years, understanding arthritis—which is not a single disease, but an umbrella term for over 100 different conditions—is essential. These conditions affect the joints and connective tissues, leading to pain, swelling, and reduced movement. The associated pain and limited function are, unfortunately, a leading cause of disability worldwide.

While there is currently no known cure for arthritis, the primary goals of modern treatment focus on reducing symptoms, limiting pain and inflammation, and preserving the function of the joint to significantly improve your quality of life.

Prefer to listen?

The Foundations of Movement: Understanding Your Joints

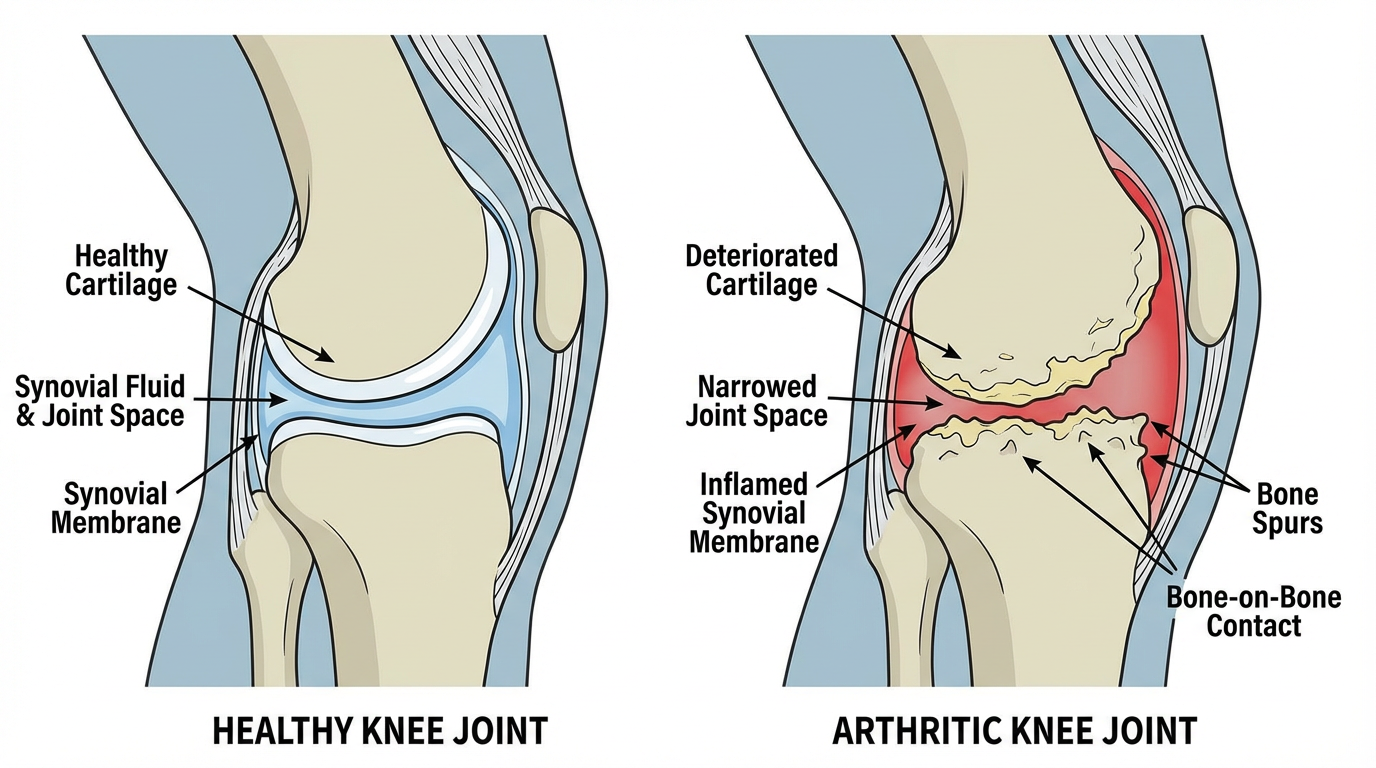

To grasp what arthritis does, it helps to understand a healthy joint. Joints are simply the points in the body where two or more bones meet. Most of the highly flexible joints in your body, known as synovial joints (like your knee or elbow), are complex structures designed for near-frictionless motion.

The critical components of a healthy joint include:

- Bones: Two or more bones meet at the joint (e.g., the femur and tibia at the knee).

- Cartilage: The ends of the bones are capped by articular cartilage, a hard, slick, white, and shiny tissue about a quarter of an inch thick in large joints. This tissue provides cushioning, absorbs shock, and allows the bony surfaces to glide against one another without damage.

- Synovial Membrane (Joint Capsule Lining): This tough membrane encloses the joint parts.

- Synovial Fluid: Contained within the joint capsule, this viscous, egg-white-like fluid acts as a lubricant, reducing friction and preventing the joint surfaces from overheating during movement.

- Ligaments and Tendons: Ligaments are tough bands of tissue connecting bones to bones, providing crucial stability to the joint. Tendons connect muscles to bones.

When arthritis strikes, one or more of these foundational elements—especially the cartilage and the synovial lining—are damaged, compromising movement and leading to the chronic pain and stiffness associated with the condition.

Symptoms and the Scope of Arthritic Pain

The symptoms of arthritis generally involve the joints themselves, though some types can affect other body systems. Since joint pain and stiffness typically worsen with age, it’s important to recognize the signs early.

Core Symptoms of Arthritis:

- Joint Pain and Stiffness: These are the most common signs. Stiffness is often worst in the morning or after periods of inactivity.

- Swelling and Warmth: Joints may become visibly swollen, warm, and red.

- Decreased Range of Motion: Arthritis often limits a joint’s ability to move normally.

Systemic Impact and Complications:

Depending on the specific type of arthritis, the condition can also cause more general issues like fatigue. Inflammatory types of arthritis, such as Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA) or Lupus, can become systemic, meaning the inflammation may affect organs such as the heart, eyes, lungs, kidneys, and skin.

Severe arthritis can significantly impact quality of life. If arthritis affects weight-bearing joints (like the hips or knees), it can prevent you from walking comfortably or sitting up straight. When the hands or arms are severely affected, performing simple daily tasks can become difficult. Over time, severe damage can cause joints to gradually lose their normal alignment and shape.

The Causes: Different Conditions, Different Mechanisms

The wide array of symptoms stems from the many different mechanisms that cause the 100-plus conditions grouped under the arthritis umbrella. The two most common types, Osteoarthritis (OA) and Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA), damage the joints in fundamentally different ways.

1. Osteoarthritis (OA)

OA is the most common form of arthritis and was historically viewed simply as a “wear-and-tear” disease.

- Mechanism: OA involves the breakdown of cartilage—the hard, slick tissue covering the ends of bones in a joint. When this protective cartilage is damaged sufficiently, the ends of the bones can rub directly against each other, causing pain and restricting movement.

- Modern Understanding: Research has revealed that OA is a disease of the entire joint, not just the cartilage. It includes changes in the bone structure, deterioration of connective tissues that hold the joint together, and inflammation of the joint lining.

- Causes: This damage occurs naturally over many years but can be hastened by a joint injury, infection, or chronic overuse.

2. Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA)

RA is an autoimmune disease. In autoimmune disorders, the body’s immune system, which is supposed to fight off infections, mistakenly attacks its own healthy tissues—a concept immunologists refer to as “self”.

- Mechanism: In RA, the immune system specifically attacks the synovial membrane (the lining of the joint capsule). This attack causes the lining to become inflamed and swollen. If the disease progresses unchecked, this inflammation eventually destroys the cartilage and bone within the joint.

- Onset: Autoimmunity in RA can start many years before joint symptoms even appear, often identifiable by the presence of autoantibodies and inflammatory factors in the blood.

- Triggers: While genetics play a role, environmental factors like viruses, stress, or smoking are thought to trigger the condition in genetically predisposed individuals.

3. Other Significant Types

- Gout: A common inflammatory arthritis caused by a metabolic issue involving high levels of uric acid in the blood. This excess uric acid forms sharp crystals in the joints (often the big toe), leading to sudden, intense pain flares.

- Ankylosing Spondylitis: A form of arthritis that causes inflammation in the spinal joints, potentially leading to chronic pain. In severe cases, spinal bones can fuse into an immobile position.

- Infectious (Septic) Arthritis: Triggered when a bacterial, viral, or fungal infection travels from another part of the body to a joint.

- Psoriatic Arthritis: A condition causing joint inflammation, typically affecting people who also have the skin disease psoriasis.

Prevalence, Age, and Gender: Who is at Risk?

Understanding the factors that increase your risk is the first step toward minimizing them.

The Role of Age

The risk of developing many forms of arthritis, including osteoarthritis, rheumatoid arthritis, and gout, increases with age. While OA is the most common form and often viewed as a consequence of many years of joint use, it is a misconception that arthritis is strictly confined to older people. Arthritis affects people of all ages, including children (Juvenile idiopathic arthritis).

The Role of Gender

Arthritis and other related rheumatic diseases are generally more common in women than in men. This disparity is particularly pronounced in inflammatory conditions:

- Rheumatoid Arthritis (RA): Women have more than double the chance of developing RA compared to men, affecting about 1% of the worldwide population.

- Gout: In contrast, most people affected by gout are men.

Illustration 1: Key Risk Factors for Arthritis

| Category | Risk Factor | Impact on Joints |

|---|---|---|

| Non-Changeable | Age | Risk for OA, RA, and Gout increases as you get older. |

| Gender/Sex | Women are more likely to develop RA; men are more likely to develop Gout. | |

| Family History (Heredity) | Some types of arthritis are linked to certain genes or run in families. | |

| Changeable | Obesity/Excess Weight | Carrying extra pounds puts significant stress on weight-bearing joints (knees, hips, spine), increasing the risk of OA. |

| Previous Joint Injury | A joint that has been injured previously, perhaps while playing a sport, is more likely to develop arthritis later. | |

| Smoking | Identified as a non-genetic risk factor for inflammatory arthritis, such as RA. | |

| Repetitive Movement (Job) | Work involving repeated bending or squatting can increase the risk of knee arthritis. |

Minimising Risk and Managing Symptoms

While certain risk factors, such as age and family history, cannot be changed, there are several powerful strategies related to lifestyle, physical activity, and medical treatment that can minimize risk, slow progression, and manage symptoms.

Section 5a: Lifestyle and Prevention Strategies

By taking proactive steps, particularly regarding weight and activity, you can significantly reduce stress on your joints and improve your health profile, often helping to prevent joint problems entirely.

- Achieve and Maintain a Healthy Weight: This is critical, as excess weight places significantly more stress on weight-bearing joints (hips and knees). Maintaining a healthy weight helps to reduce this joint pressure, thereby potentially reducing pain and the risk of developing OA.

- Stay Active with Low-Impact Exercise: Regular physical activity is one of the most effective ways to treat and manage arthritis. Exercise helps in multiple ways: it reduces joint pain and stiffness, keeps surrounding muscles strong, improves fitness, and positively affects mental health and sleep. It is important to find the right type and level of activity, focusing on low-impact choices such as walking, swimming, cycling, yoga, tai chi, aqua aerobics, or strength training.

- Eat a Healthy, Balanced Diet: A healthy diet supports overall wellbeing and helps maintain a healthy weight. For those managing inflammatory types of arthritis, consuming a diet rich in fruits, vegetables, whole grains, and olive oil, while limiting red meat, highly processed foods, and sugar, may help reduce inflammation. If you have gout, you should follow specific advice regarding avoiding alcohol and certain high-purine foods.

- Avoid Smoking: Smoking is recognized as a non-genetic factor that can trigger inflammatory arthritis like RA and should be avoided.

- Protect Your Joints: It is beneficial to switch between activity and rest to reduce undue stress on your joints.

Illustration 2: Lifestyle Strategies for Joint Health

| Strategy Area | Key Actions for Joint Protection | Benefits |

|---|---|---|

| Weight Management | Maintain a healthy weight and body composition. | Reduces pressure on the knees, hips, and spine. |

| Physical Activity | Engage in regular, low-impact activities (e.g., swimming, walking, yoga). | Strengthens muscles, improves flexibility, reduces pain and stiffness. |

| Diet and Nutrition | Eat a healthy, balanced diet; consider limiting processed foods, red meat, and sugar. Follow specific dietary advice if managing gout. | Supports overall health, aids in weight control, and may help reduce inflammation. |

| Habits | Quit smoking entirely. | Removes a known risk factor, particularly for autoimmune inflammatory arthritis like RA. |

Section 5b: Managing Symptoms with Treatment Options

There is no known cure for arthritis; therefore, treatment is individualized and focuses on a combination of pharmacological, physical, and surgical methods aimed at controlling symptoms and preserving function.

1. Pharmacological Management:

Medicines offer both short-term relief and long-term management, particularly for inflammatory forms:

- Short-Term Pain Relievers: Over-the-counter options such as acetaminophen, aspirin, ibuprofen, or other nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory medicines (NSAIDs) can provide quick relief from pain and inflammation. However, long-term use of certain anti-inflammatory medicines should be closely managed with your provider due to potential side effects like stomach bleeding.

- Corticosteroids: Medications like prednisone reduce inflammation and swelling and can be administered orally or via injection.

- Disease-Modifying Anti-Rheumatic Drugs (DMARDs): For autoimmune types like RA, prescription medicines (including methotrexate, hydroxychloroquine, and sulfasalazine) are used long-term. These drugs aim to slow the disease progression and address the underlying immune system issues.

- Advanced Therapies: Biologic therapies represent an advanced treatment approach for inflammatory diseases such as RA, often working by blocking specific inflammatory proteins (like TNF-alpha) that drive inflammation.

- Joint Injections: For osteoarthritis, hyaluronic acid (a component of joint fluid that breaks down with the condition) can sometimes be injected into the joint, such as the knee, to help ease symptoms. For gout, uric acid-lowering drugs are often prescribed for repeated or severe flares.

2. Physical and Therapeutic Management:

These strategies are crucial for improving mobility and managing daily tasks:

- Professional Therapy: A multidisciplinary team often manages arthritis. Professionals such as a physiatrist, physical therapist, or exercise physiologist can guide you on the best activities and exercises to reduce joint pain and stiffness. An occupational therapist can provide valuable advice on modifying daily activities and using adaptive equipment to protect your joints and manage daily tasks more easily.

- Heat and Cold Therapy: Applying moist heat (like a warm bath or shower) or dry heat (heating pad) can ease pain, while cold (an ice pack wrapped in a thin towel) can reduce swelling and pain.

- Pain Management Techniques: Complementary methods may help manage pain, including massage, acupuncture (performed by a licensed provider), and Transcutaneous Electrical Nerve Stimulation (TENS), which uses mild electrical pulses to block pain signals. Mindfulness techniques and meditation may also provide relief.

- Assistive Devices and Equipment: Using assistive devices such as canes, crutches, and walkers can help reduce stress on specific joints and improve balance. Adaptive equipment like reachers and grabbers, as well as dressing aids, can help you carry out routine tasks without excessive straining.

3. Surgical Options:

When joint damage is severe, leading to significantly limited mobility and affecting quality of life, surgery may be recommended.

- Procedures: Surgical options vary depending on the affected joints and can include arthroscopy (a minimally invasive procedure), joint fusion, or complete joint replacement.

- Recovery: A full recovery following surgery can take up to six months, and a dedicated rehabilitation program is an essential component of the treatment plan.

Illustration 3: Comprehensive Arthritis Treatment Overview

| Treatment Category | Specific Methods | Primary Goal |

|---|---|---|

| Pharmaceuticals | NSAIDs, Acetaminophen, Corticosteroids (Prednisone), DMARDs (Methotrexate), Biologic Therapies, Hyaluronic Acid injections. | Reduce pain and inflammation (short-term); slow disease progression and manage immune response (long-term). |

| Physical/Lifestyle | Physical Therapy, Occupational Therapy, Exercise (low-impact, strength training), Weight Loss, Joint protection strategies. | Preserve joint function, increase flexibility, strengthen supporting muscles, and reduce stress on joints. |

| Complementary Pain Relief | Heat/Cold application, Massage, Acupuncture, TENS, Mindfulness/Meditation. | Ease pain and stiffness, improve blood flow, and modify pain perception. |

| Adaptive Support | Canes, Crutches, Walkers, Reachers, Dressing Aids. | Reduce strain on joints, improve balance, and maintain independence in daily tasks. |

| Surgical Interventions | Arthroscopy, Joint Fusion, Total Joint Replacement. | Repair severely damaged joints, increase mobility, and alleviate chronic pain when damage is advanced. |

Conclusion: Taking Control of Your Joint Health

Arthritis remains a widespread challenge, especially for those in or approaching retirement, but it is not an inevitable sentence of immobility. By recognizing the common symptoms—pain, swelling, and stiffness—and understanding the distinct causes of different types, you are better equipped to advocate for your health. Since there is no single cure, the path to a full and active retirement depends on early diagnosis and a comprehensive, personalized treatment plan.

Crucially, lifestyle changes are not merely supplements but core components of successful management. Maintaining a healthy weight, remaining physically active with suitable low-impact exercises, and protecting your joints through assistive devices and a balanced routine are all essential steps. By working closely with your healthcare team, including your doctor, physical therapist, and occupational therapist, you can maximize your joint function, reduce discomfort, and sustain the quality of life you desire during your retirement years.