Last Updated on June 30, 2025 by Julian Espinosa

Aging happy must have been something of an impossible proposition in the days gone by. Back in the days when living to old age was uncommon, there weren’t many significant writings about aging. Those that did exist were written by authors who themselves were – by our standards – quite indifferent to the difficulties of aging.

Johnathan Swift was roughly fifty-five when he depicted the immortal but sickly Struldbruggs in Gulliver’s Travels. Chaucer was about fifty when he came up with “The Merchant’s Tale.” Shakespeare must have been around forty-one or forty-two when he wrote ‘King Lear.’

Is Aging Happy Getting Easier?

Now, you might argue that the age of forty was not so young in Shakespeare’s time. But Shakespeare survived birth in the 1560s, when many women died from blood loss during labor. Stillbirth was a common occurrence, too, of course, as tools like forceps had not been invented yet. Later on, Shakespeare somehow lived through a time when one had to deal with disease, war, and epidemic, as well – all of which reduce one’s odds of aging, regardless of the era.

No, aging happy was not an easy accomplishment in Elizabethan England. But by modern standards, 40 is certainly not old! In fact, throughout history, life expectancy was generally dismal. Aging happy was almost impossible. And it certainly was not easier. Most never made it. This might clarify why there’s a scarcity of books by people over 50 years old in classical literature about aging.

We’ll find many books about school days, young love, young men in war, and also all sorts of family misfortunes. But, in the old days, there simply were not enough older people to share their stories. Aging happy was not as easy as it is now as it was back then.

Aging Is Not So Rare These Days

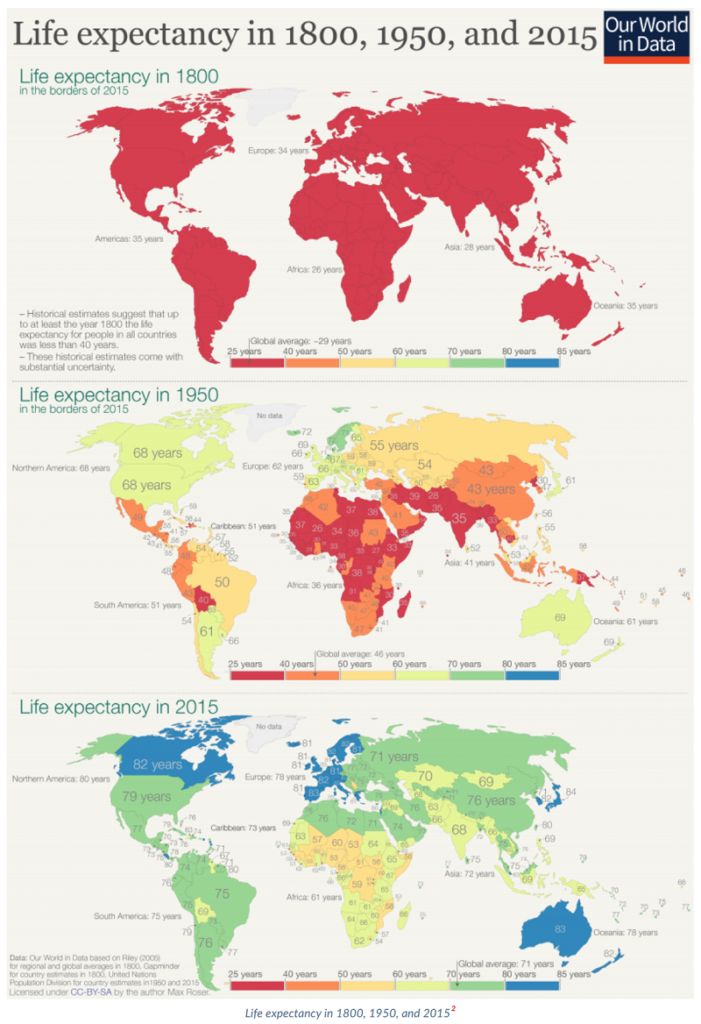

That is certainly no longer the case today. New research suggests that at the beginning of the 19th century no country in the world had a life expectancy longer than 50 years old. Just about everyone in the world lived in extreme poverty, according to researchers behind the “Our World in Data” website, a project of the Global Change Data Lab.

That is because we had very little medical and technical knowledge, and in all countries our ancestors had to prepare for an early death. Over the next 150 years, some parts of the world achieved substantial health improvements. In 1950, the life expectancy for newborns was already over 60 years in the Western World, Oceania, and parts of South America.

Today, most people in the world can expect to live as long as those in the very richest countries in 1950. The United Nations estimate a global average life expectancy of 72.6 years in 2019.

The Surging Interest in Aging Happy

So, we read about seniors enjoying adventures like traveling, volunteering, falling in love, learning new skills, and more. It seems nobody wants to talk negatively about aging. Nora Ephron’s “I Feel Bad About My Neck” attempts it, but it’s too cleverly sad and does not strike the perceptive reader as genuine.

We also have upbeat messages from books like Alan D. Castel’s “Better with Age: The Psychology of Successful Aging.” All these accounts appear to reassure us that aging happy just takes a little more effort putting more to stay young. But is that really an easy thing to achieve for retirees these days?

The Defining Transitions of Our Later Years

The defining transitions of late life – retirement, grandparenthood – are biologically and culturally determined. For example, retirement age is now a strongly contested issue. Psychotherapists know some of the consequences of these legally defined limits.

They recognize the psychological mechanisms that may be released by definite exclusion from work life. Aging can be a miserable and challenging experience. Physical health also becomes a prominent concern for many retirees. The wear and tear on the body over the years may lead to various health issues, which can make aging happy challenging.

Simple tasks like walking or climbing stairs can become arduous, which affects the independence and quality of life. Chronic illnesses often make an appearance in old age, requiring ongoing medication and medical attention. These can sometimes be difficult to manage, requiring regular check-ups and spending.

The financial strain of healthcare expenses adds an additional layer of difficulty to the prospects of aging happy. This is especially true for seniors on fixed incomes. Loneliness and social isolation also emerge as significant hurdles for aging happy. As friends and family members may pass away or live far away, older individuals may find themselves lacking companionship.

New technology can help seniors connect, no doubt, but many retirees find all a but a few new technology gadgets intimidating.

A Positive Spin?

Yet even psychologist Mary Pipher, who specializes in helping women over sixty whose minds and bodies are often undervalued, urges seniors to see everything in a positive light. Aging happy is among the most meaningful objectives we can achieve in life, she seems to say.

Is aging a matter of productivity, then? In previous decades, the Japanese government had advanced a policy that assumed that aging happy meant aging productively. For example, often regarded as one of the greatest inventors in history, Thomas Edison, continued to innovate well into his later years.

Filing patents into his eighties, contributing significantly to the development of the phonograph and motion pictures, and leaving an indelible mark on technology. That supposedly was the path to aging happy. But gradually, researchers began to realize that this tended to coerce seniors to contribute to contribute to society — and to do so with crippling detrimental consequences.

Today, the Japanese government has reversed the policy and espoused a view that the best route to aging happy is to allow older people the freedom to make that choice.

Why Modern Seniors Are Pioneering Happiness

This demographic shift has created something entirely new: a large population of people who have the luxury of time, often good health, and frequently the financial means to explore what brings them genuine satisfaction. Unlike their ancestors who were primarily concerned with basic survival, today’s seniors can focus on growth, contribution, and personal fulfillment.

The surge in books, research, and resources about thriving in later life reflects this reality. Authors like Alan D. Castel in “Better with Age: The Psychology of Successful Aging” aren’t just offering platitudes—they’re documenting real phenomena that researchers are observing across cultures and continents.

The Science Behind Senior Contentment

Recent happiness research reveals something fascinating about how our emotional lives evolve. In the United States, people aged 60 and older report high levels of well-being compared to younger people, with the country ranking in the top 10 globally for happiness in this age group. This contradicts many assumptions about the challenges of physical decline and life transitions.

The famous “U-shaped happiness curve” that researchers David Blanchflower and Andrew Oswald first identified in 2008 continues to hold true in modern studies. Research confirms this U-shape across 145 countries, with happiness reaching its lowest point around age 50 before rising again in later years. However, the 2024 World Happiness Report shows that while globally young people aged 15-24 still report higher life satisfaction than mature adults, this gap is narrowing in Europe and has recently reversed in North America.

Aging Happy: Is Happiness an Easy Choice to Make?

This writer’s grandmother passed away at the age of 102. She had just celebrated her final birthday when I last came to visit her. She was living with an aunt of mine and was remarkably strong for a woman of her age. But she was not feeling well that day. She had to be wheelchaired back into her bedroom in the afternoon. She had dozed off in bed as I was about to leave, but her eyes fluttered open just in time to tell me something that I have never forgotten.

“Good-bye for now,” I told her. “I’ll see you again next week.”

“What’s the problem, boy,” she said from the bed. “Why do you look so glum?”

“Oh, nothing.”

“Go on, tell me,” she said. “Come here and tell me.”

I pulled a chair by her bed and sat down. “Life is hard,” I said to her. “I’ve got a lot of things in mind.”

She chuckled. “Oh, yes, life is hard,” she said. “But every last drop of it is wonderful. Be thankful.”

That was the last time I ever saw her. The fact of the matter is that the link between happiness and aging is almost universally acknowledged as true. The perspective that nature is always correct found a compelling advocate in the Roman statesman Cicero. He was sixty-two when he penned “De Senectute,” loosely translated as “How to Grow Old.”

This noteworthy work earned praise from American president’s John Adams, who lived to be ninety, and Benjamin Franklin, who lived to be eighty-four.

Happiness Sits on a U-Shaped Curve

In a pivotal 1995 study, researchers at Fordham University sorted over 32,000 Americans into various age groups. Astonishingly, 38 percent of seniors aged 68 to 77 reported feeling “very happy,” a significantly higher proportion compared to their younger counterparts.

A more recent study conducted by researchers at the University of Southern Denmark involved over 10,000 Danes aged 45 and older. The researchers discovered that despite seniors facing health challenges, their reported levels of happiness were at least on par with those of younger adults.

This sense of contentment and happiness isn’t confined to seniors in their 70s and 80s but extends even to centenarians. Are the times making it easier for seniors to age happy? Based on a Gallup survey from 2011, happiness aligns with the U-shaped curve initially introduced in a 2008 study by economists David Blanchflower and Andrew Oswald. Their research revealed that people experience the highest sense of well-being in childhood and old age, with a noticeable dip occurring around midlife.

More pointed scientific research seems to support this theory. A 2012 study involving British centenarians challenged expectations, as these individuals expressed that “it felt good to be 100 years of age.” Peter Martin, a gerontologist at Iowa State University who has extensively interviewed individuals aged 100 and above, notes that the majority of them leave him with the impression that old age can indeed be a happy and fulfilling time.

These research findings pose a paradox: despite confronting difficulties and physical decline, there appears to be something about old age that makes aging happy a little easier these days.

The Unique Advantages of Your Golden Years

What creates this upward trend in happiness as we mature? Research points to several key factors:

Emotional Regulation Mastery: Decades of life experience teach us how to manage our emotional responses more effectively. We become better at recognizing what triggers stress and developing healthy coping mechanisms.

Perspective and Priorities: Having weathered various life storms, seniors often develop clearer priorities about what truly matters. This leads to less time wasted on trivial concerns and more energy devoted to meaningful pursuits.

Reduced Social Pressure: Freedom from career advancement pressures, child-rearing responsibilities, and the need to “prove oneself” creates space for authentic self-expression and exploration.

Present-Moment Awareness: Research consistently shows that mature adults become more skilled at focusing on positive aspects of their current experiences rather than dwelling on past regrets or future anxieties.

Navigating Real Challenges with Resilience

This doesn’t mean the senior years are without challenges. Health concerns, financial worries, and social isolation remain real issues that many face. The loss of friends and family members can create profound grief. Physical limitations may require significant life adjustments.

However, what’s remarkable is how effectively many seniors navigate these difficulties. Rather than being overwhelmed by challenges, they often develop sophisticated strategies for maintaining emotional equilibrium. This might involve:

- Building strong support networks through community involvement

- Adapting daily routines to accommodate physical changes

- Finding new sources of purpose and meaning

- Cultivating gratitude practices that highlight life’s positive aspects

Technology: Bridge or Barrier?

While some seniors find new technology intimidating, many are discovering how digital tools can enhance their connections and opportunities. Video calling helps maintain family relationships across distances. Online communities provide access to people with shared interests. Digital platforms offer learning opportunities that previous generations never had.

The key is approaching technology as a tool for connection rather than a requirement for relevance. Those who embrace useful technologies while ignoring unnecessary complexity often find the perfect balance.

Redefining Productivity and Purpose

Japan’s policy evolution regarding senior citizens offers valuable insights. Initially promoting “productive aging”—expecting seniors to continue contributing to society in traditional ways—the government eventually recognized this approach could be harmful. The revised approach acknowledges that happiness in later life comes from having the freedom to choose how to spend one’s time and energy.

This shift reflects a broader understanding that purpose doesn’t have to mean traditional productivity. For some, purpose might involve grandparenting, volunteering, creative pursuits, or simply being a source of wisdom and support for others. The diversity of meaningful ways to spend our golden years is one of their greatest gifts.

Wisdom from Lived Experience

Personal stories often illuminate these research findings most powerfully. Consider the centenarian grandmother mentioned in the original article, who at 102 could still find wonder in every aspect of life: “Life is hard, but every last drop of it is wonderful. Be thankful.”

This perspective—the ability to acknowledge difficulty while simultaneously embracing gratitude—appears frequently among happy seniors. It’s not about denying challenges or forcing positivity, but rather developing the emotional sophistication to hold multiple truths simultaneously.

The Grace and Fascination of Senior Years

Consistent results from over a decade of research underscore the remarkable ability of most elderly adults to focus on the positive. This applies to whether they are reflecting on their memories or contemplating the present moment. This makes aging happy a good deal less difficult, researchers argue.

It seems that, contrary to longstanding misconceptions, the later stages of life offer a multitude of reasons for seniors to embrace happiness. Scientists and researchers have offered multiple explanations to the positivity effect seen in older individuals, including theories involving age-related changes in the brain.

However, an increasing number of experts are converging on the idea that happiness for seniors is, at its core, a daily choice. Research seems to suggest that those with positive mindsets in their later years employ effective strategies to minimize the impact of negative experiences.

In essence, aging happy seems to hinge largely on the ability to highlight and accentuate the positive aspects of life, researchers claim.

From the wealth of experience and wisdom to the freedom from career pressures, the joy of meaningful relationships, an appreciation for simplicity, the potential for personal growth, and a focus on health and wellness, our senior years offer a tapestry of reasons to find fulfillment.

By celebrating these aspects, perhaps we can live a life filled with purpose and joy, we are told. But why do we have this suspicion that aging happy just might be as difficult a goal as it was during Shakespeare’s time? Perhaps we can always hope that it’s easier now. We may never find out. We’d need a time-machine to find out. But the allure of the idea is certainly tempting.

As Walt Whitman, who remained unmarried all his life and lived to the age of seventy-two, eloquently advocated, “YOUTH, large, lusty, loving—youth full of grace, force, fascination, do you know that Old Age may come after you with equal grace, force, fascination?”

What do you think?